Summary Background

SUMMARY BACKGROUND

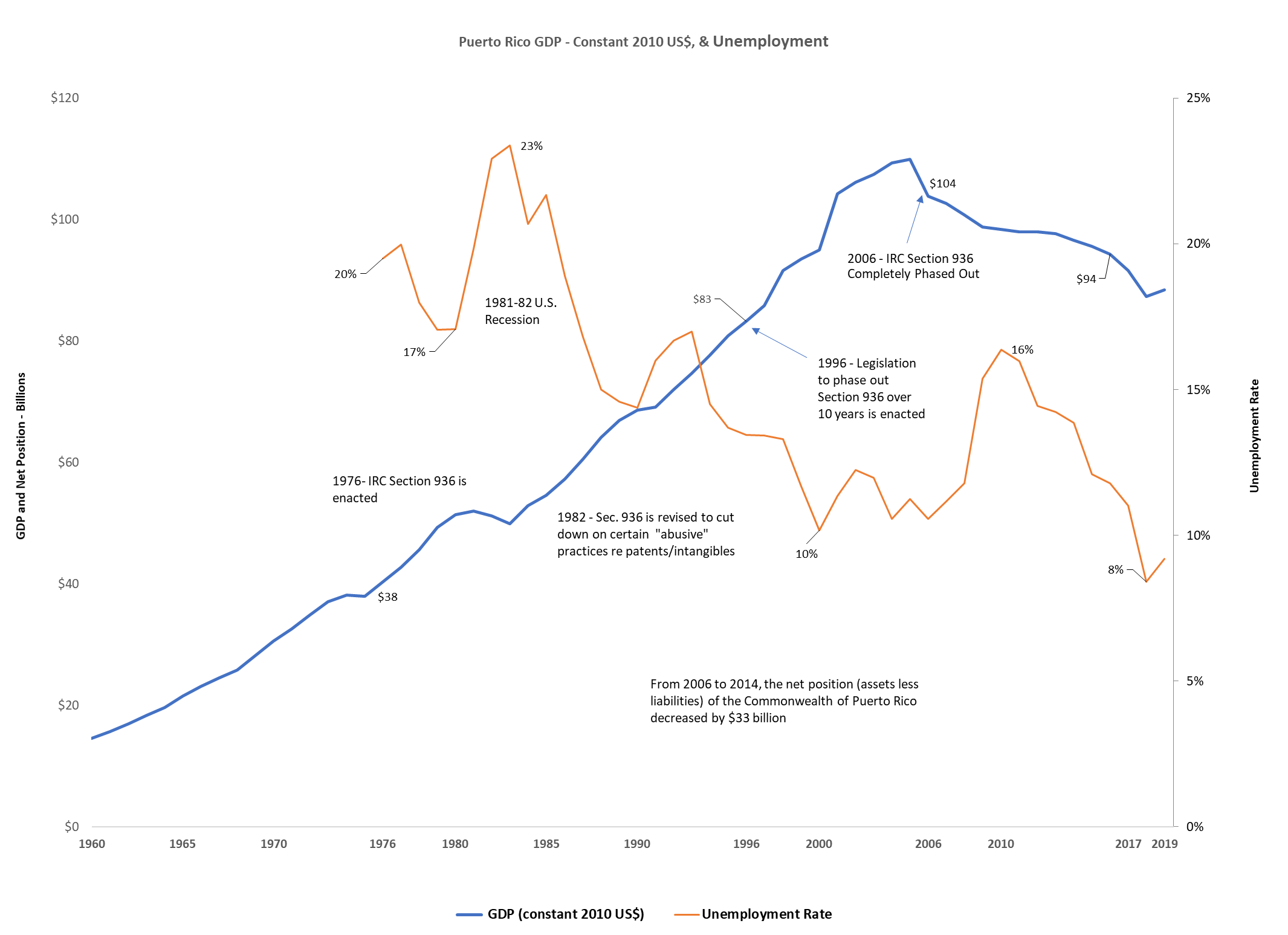

Puerto Rico’s current economic situation can also be attributed to a history of incentives that have come and gone at various intervals over the last 70 years when Puerto Rico, as well as the SPREDD region, began to transform from an agrarian society to an industrialized economy. The Revenue Act of 1921 provided a tax exemption to all U.S. corporations receiving income from U.S. possessions or territories; however, at the time, Puerto Rico’s local income taxes essentially nullified the federal tax incentives.

Puerto Rico started to make inroads as an industrialized territory during World War II. After seeing the benefits of moving to an industrialized society, Puerto Rico’s legislature passed the Industrial Incentives Act of 1948, also known as “Operation Bootstrap,” which exempted U.S. corporations from most Puerto Rican taxes, thus enabling U.S. corporations to take advantage of the Revenue Act of 1921. The U.S. supported this effort, viewing Puerto Rico as a vital capitalist outpost in the Caribbean.[1]

Operation Bootstrap successfully industrialized Puerto Rico and also shifted the economy’s base from agriculture to industry in less than 20 years. However, the industrialization of Puerto Rico did little to expand the workforce, as many manufacturers were locked into global supply chains; therefore, there were limited multiplier impacts on other jobs and local business creation.[2] The Possession Tax Credit created in 1921 evolved into section 936 in 1976. In 1992, the Congressional Budget Office estimated section 936 would cost taxpayers $15 billion for the five years covering the 1993-1997 fiscal years. Legislation phasing out section 936 over the next decade was signed into law in 1996.

As demonstrated in Chart 2, the economy of Puerto Rico, as well as the SPREDD region, have expanded and contracted to a significant extent based on similar expansions and erosions of incentives. Key components of plans for economic growth and resiliency, as well as this CEDS focus on growing industries able to flourish in the region absent of incentives. For example, during the 30 years section, 936 was in place in some capacity, the unemployment rate was never lower than 10%. Decreases in the unemployment rate during 2018 and 2019 are attributed to decreases in the labor force, as opposed to new job creation.

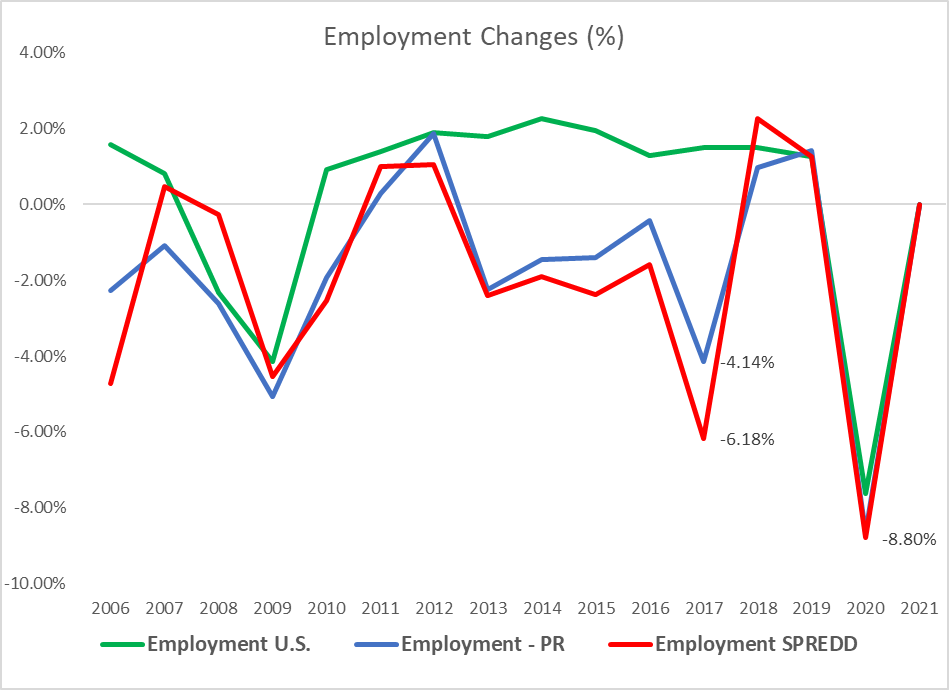

The prolonged recession, compounded by Hurricanes Irma and Maria, earthquakes, and COVID-19 has led to significant job losses for Puerto Rico and the SPREDD region. Since 2006, Puerto Rico has lost nearly 239,000 jobs or 22% of its employment base.[3]

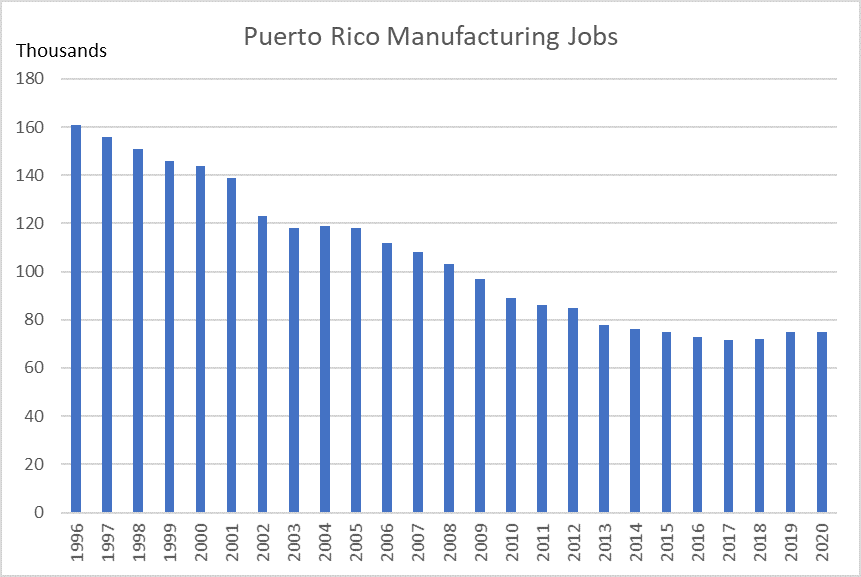

As shown in Chart 3, Puerto Rico has lost 86,000 manufacturing jobs since legislation to phase out section 936 was signed into law in 1996. (Because of BLS data restrictions that may identify information about specific firms, historical data on the manufacturing base of SPREED’s region is not available.)

WHY IS THIS IMPORTANT?

Discuss resiliency issues and measures here.

Add a chart component pack for topic x

It is encouraging to note that manufacturing employment in Puerto Rico, as well as the region, has increased since 2017. The increase in manufacturing jobs also coincides with the passage of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) in late 2017, which among other things made it more difficult for U.S. companies to benefit from very low foreign income tax rates. Even though Puerto Rico is part of the U.S., it remains a foreign jurisdiction for U.S. income taxes, which is a key competitive strength. Although many feared the impact TCJA would have on Puerto Rico, even referring to the legislation as “the Third Hurricane,” manufacturing jobs have increased since its passage and now exceeds pre–Hurricane Maria levels.

With respect to total jobs, the SPREDD region has fared similarly since 2006, losing nearly 18,000 jobs, or 22% of its employment base, as outlined in Chart 4. Puerto RICO and SPREDD have both lost nearly 9% of its jobs from the end of 2019 to the Third Quarter of 2020; indicating the economic impacts of COVID-19 appear to be worse than the economic setbacks caused by Hurricanes Irma and Maria. (See Chart 5)

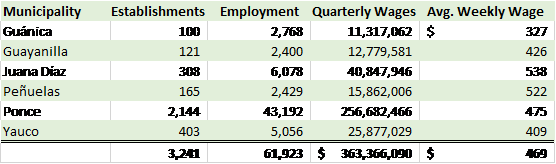

The current employment in the region by municipality is summarized in Table 2.

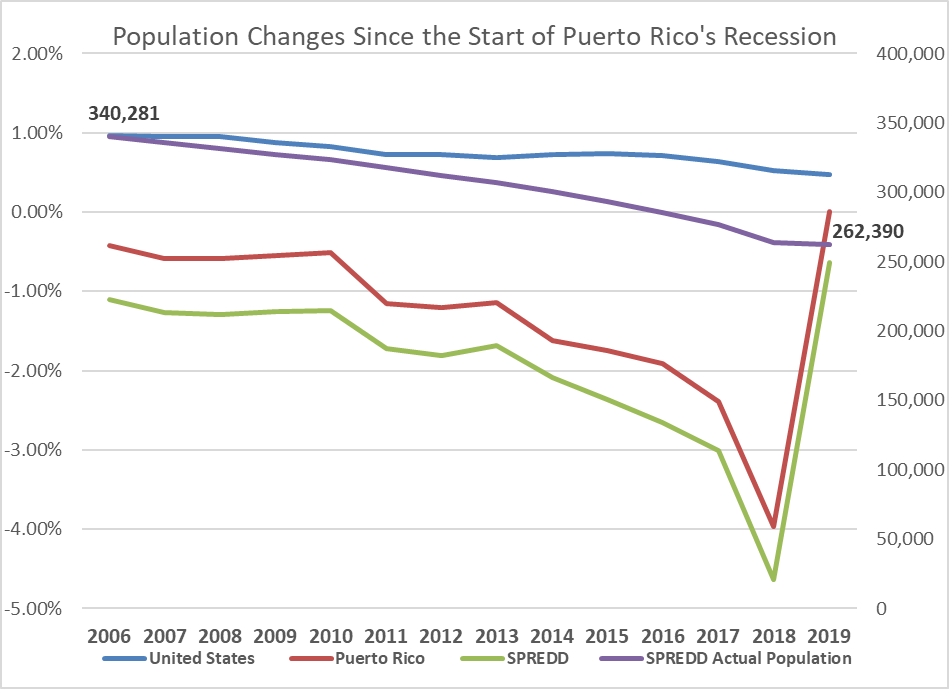

Population loss is a consequence of job loss. Pew Research has stated that employment opportunities are the primary driver of out-migration from Puerto Rico. Since 2006, SPREDD’s region has realized a 23% decrease in population, which equates to nearly 79,000 residents.[4] In fact, SPREDD’s region has realized population losses nearly every year since 2006, while Puerto Rico has seen a decrease in population of 16% during this timeframe.[5]

Poverty rates have also increased as a direct result of the enduring recession, job loss, and outmigration. According to the latest Census data, Puerto Rico is burdened with a poverty rate of 43.1%, which is 3.3x the national rate of 13.1, and more than twice as much as the poorest state (Mississippi). The six municipalities comprising SPREDD have a poverty rate of 52.6%.[6]

[1] U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics QCEW

[2] Reuters, December 20, 2016: How dependence on corporate tax breaks corroded Puerto Rico’s economy

[3] Reuters

[4] U.S. Census Bureau ACS 5-year 2019. For additional details, see Table 7 on Page 15.

[5] U.S. Census Intercensal Estimates

[6] U.S. Census Intercensal Estimates